Wearable Tech - Are screens changing?

How many tech pieces do you have on you without a screen right now?

Wearable technology has long been perceived as merely materialistic status symbols for the wealthy, tech-obsessed elite. However, as we witness the futuristic, albeit slightly nightmarish, emergence of innovations such as the Apple Vision Pro, a deeper exploration suggests a potential shift in consumer priorities. It causes us to question: what do we actually want from our technology now? As most consumers feel distracted and overwhelmed in a visually overstimulating culture, are we pushing the boundaries of what a ‘screen’ can mean, and instead moving to a more responsive, auto-centric world? While the Vision Pro is still, in my books, a creation of techbro culture, it does beg the question of whether people want to move away from the ubiquitous screens in our personal and professional lives to a less physically restrictive tech culture.

Wearable technology has evolved beyond the confines of conventional smartwatches and headphones. Their innovation lies in challenging consumption norms, reflecting a disillusionment of our screen-obsessed culture. Screens are present in every facet of our life, even spurring the meme itself ‘can’t wait for good screen time over bad screen time’ (i.e. scrolling TikTok after spending all day on my work computer). I even found myself telling my friends I had a super chill Friday night, which consisted of me watching Love is Blind on my TV while simultaneously switching between scrolling TikTok on my phone and Twitter on my laptop. As we’ve discussed before, people are nursing a growing desire to disconnect from the omnipresent ‘digital sphere’ and go outside, get offline, go ‘touch grass.’ Screens embody the physical barrier to the outside, a confine to our yearning for physical connection. And we also know, deep down, how truly difficult it would be to live our lives without the resources screens provide us. Work, staying connected to friends and family, banking, shopping - screens present themselves as a window to all of this.

So, will screens one day become an archaic memory of being online? As screens become increasingly omnipresent, wearable technology can introduce a paradigm shift towards audio and motion-centric response culture, thus a less physically restrictive culture of consumption. We’re so visually overloaded with a barrage of information and content daily, perhaps there is room for a shift towards a more integrated use of our senses. Apple’s Vision Pro still feels slightly yucky to me, as videos of techbros clog my social media feeds (we’ve seen them, sitting entirely detached from reality in public spaces with £3,500 ski goggles on, aimlessly scrolling their fingers through midair), but perhaps it's one step towards turning the outside world around us into one big screen and integrating our physical body responses into it. Right now, we’re developing and modelling new technology hyper-focussed on only one part of our nervous system, the brain, thus flattening innovation. All tech is unintentionally designed to capture human attention, and we’re visually overstimulating one tiny part of it. It’s burning us out, it’s overwhelming us.

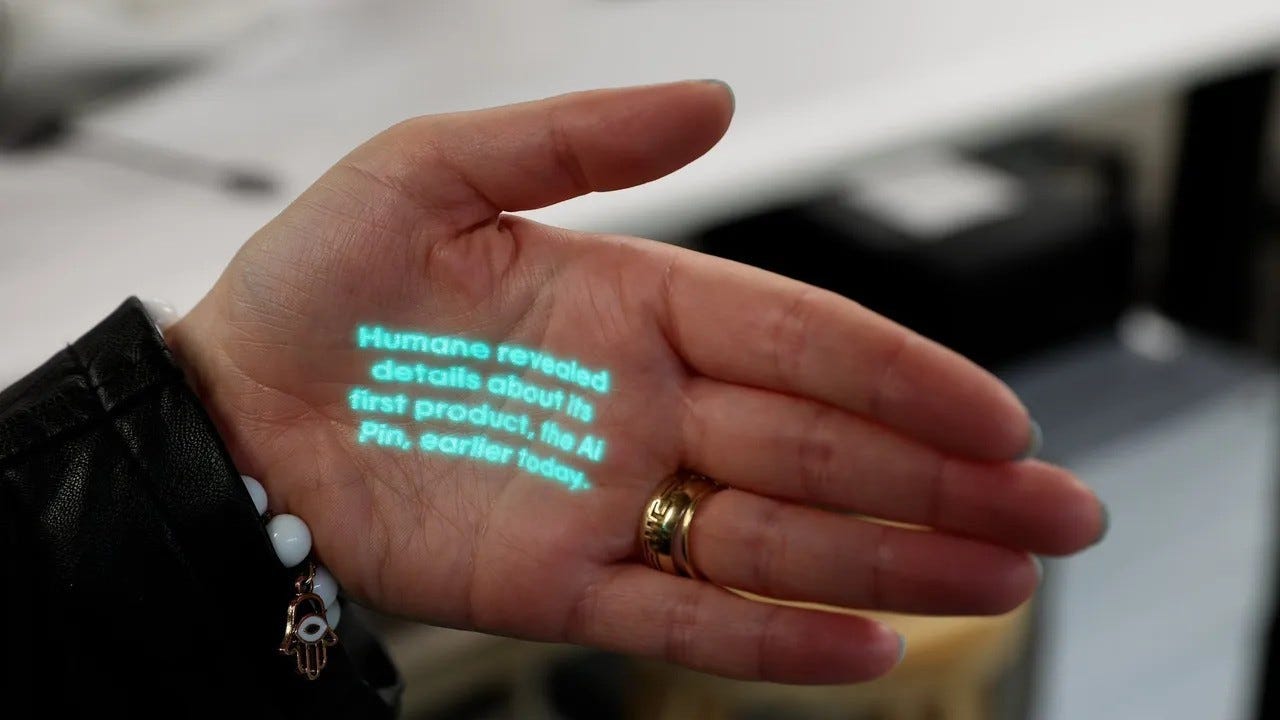

Wearable devices like AI Pin, which as described in The Verge, “You clip it to your shirt, talk to it, and it uses generative AI to answer. It’s a standalone device with its own SIM card, and there’s no screen — just vibes. That, and a little laser that projects menus and text onto your palm”, and even bluetooth headphones with Wi-Fi capabilities provide avenues for interaction through speech, location, and movement, offering a respite from the ever-so-present glowing blue-lit screens we’ve come to know (and love?). They’re not perfect, and the dominance of screens still feels slightly inescapable (a lot of these devices have to be set up through a screen). That being said, they seem to be addressing the attention economy crisis by ushering in a new age of audio soundscaping and incorporating the human body, providing, albeit however temporary, a liberation from constant visual bombardment.

Wearable technology has made several attempts to redefine our interaction and capture our ever-fleeting attention in the digital realm, with… varying degrees of success. From immersive VR goggles (I tried them once, they gave me what I can only describe as vertigo) and Google Glass, these innovations have attempted to break away from a conventional screen interface, and position our real world as a ‘screen’ in itself. However, these mainstream adaptations never truly lived up to their own hype, nor became permanent fixtures in culture. Perhaps they came a bit too soon, just a few steps ahead of our impending, inevitable screen addictions? Eesh. Despite these former setbacks, the emergence of new products like Apple Watch and Ray-Ban’s foray into smart glasses suggested an ongoing exploration of the potential applications, and perhaps acceptance, of wearable tech. They challenged the conventional limits of screens, allowing a role for them in the real world that wasn’t so visually restrictive.

Major tech titans are now experimenting with hardware that, by proxy, transforms our world into a colossal screen. We should question whether we prefer an immersive screen-based existence, or whether we want interfaces that seamlessly align with our body cues, such as speech and movement. Or, can these two things coexist? While our current state of wearable technology, epitomised by the Vision Pro, may still feel faulty, exclusionary, and somewhat dystopian, it also signifies a wider cultural shift in tech innovation.

While the faults of current iterations should not be overlooked, the ongoing evolution of wearable technology suggests a potential trajectory away from screens, emphasising body cues and voice as the controls for our digital interactions. As we redefine our relationship with this tech and what screens mean in our lives, we can ask: are these innovations just a flash in the pan, some funky gadgets, or are they helping to alleviate our screen addiction entirely?